Introduction

One of my deepest joys in life is building companies in unfamiliar industries where I start with 0 domain knowledge. Two things excite me about this process. The first is discovering how a particular industry powers some aspect of the world previously unknown to me. The second is imagining the futures that can be unlocked by introducing novel technologies to an industry.

From 2016 to 2020, I launched 2 companies. Both were accepted into YCombinator. The first was Ikigai, computational drug-discovery company for Alzheimer's Disease (accepted YC S18).1 The second was basis, a CRM for construction trade contractors (accepted YC S19). I launched both companies while I worked at Uber ATG as a software engineer building self-driving cars. In both cases, I started with 0 experience in the healthcare or construction industry.

Here's my personal process for discovering ideas and getting ideas off the ground.

Talk to people

A startup succeeds by building a product that solves a problem so most first-time founders will start by asking

What problem do I solve?

Actually that's the wrong question to start with. The right question is

What process can I follow to discover interesting problems?

The first question is difficult to answer for founders with 0 insights about an industry. To see this, try to answer the following questions for an unfamiliar industry like pest-control or waste management.

- What are the interesting problems in this space?

- Which problems will people pay money for?

- Why do people care are about these problems?

- What is the root-cause of these problems?

- What do potential solutions look like and why haven't they been built?

- How might you launch a solution and generate initial traction?

Most people are stuck. The takeaway is that without insight, there cannot be innovation.

To get unstuck, talk to people.

To find problems, talk to people.

To generate insights, talk to people.

When Kevin and I founded basis, we had 0 construction experience. To start, we sourced 20 conversations with construction experts in our network. We talked to owners, general contractors, project managers, estimators and superintendents and asked them simple questions.

- What does your day-to-day look like?

- What was something that frustrated you last week, last month?

- Why did that process frustrate you?

- What tools and processes do you use to get around those frustrations?

Very quickly, we started hearing things like

"I hate arguing with subcontractors over percentage completed"

"I have to drive 3 hours each week to inspect the site because I'm paranoid people will slack off and take shortcuts"

"I enter in the same deadline in 3 different spreadsheets"

Over time, we heard the same stories from multiple people and these stories surfaced themes in construction: cost disputes, late payments, excessive data-entry. These same themes would go on to inspire our initial ideas.

It turns out the process for identifying promising startup ideas is not complicated. Talk to lots of people and let those conversations inspire you. This works because conversations are raw-unfiltered looks into how an industry operates. They will contain stories of day-to-day frustrations that industry experts face; these frustrations are clues for possible areas for innovation. Think of each conversation as a puzzle piece and the job of a founder as compiling those pieces into a promising startup idea.

My experiences with launching Ikigai and basis have taught me that a rigorous process for learning matters far more than any single idea. A reliable process for learning enables founders to be deliberate about iterating towards good ideas, rather than leave this process to chance.

What makes launching in non-familiar industries so difficult is the chicken-and-egg problem of "how do I get people to talk to me and share their wisdom even if I don't have anything to offer immediately?". I wish I had a playbook for this problem. Unfortunately, I don't because sourcing conversations is more art than science - an art that changes based on industry, a founder's network and circumstances.

Just find any reason to launch

At some point, learning stagnates from conversations alone and you have to launch a product to actually build a company.

While visionary founders can design products based on empathy for a specific problem and the users that face that problem, non-visionary founders must build products for unfamiliar audiences.¹ As a result, the first product a non-visionary founder launches is often misguided, especially if the product is based solely on intuition from conversations. There are simply product insights that cannot be intuited from conversations alone.

- Is this problem actually painful to the user or do they just think that it is?

- Does the product solve an industry problem or just a company-specific problem?

- Does the product solve the pain-point effectively?

- Is the product easy to use?

- Can the product overcome entrenched processes and gain adoption?

Early-on, non-visionary founders need a sandbox that enables them to launch products (potentially multiple), iterate and learn from users in the industry. This is another chicken-and-egg problem; you need a sandbox to learn, but it is difficult to build a sandbox if you don't have much to offer upfront.

To build sandboxes for Ikigai and basis, I relied on a technique called a minimum launchable reason, which just means find any reason to launch a product/service/collaboration/project in your target industry.

I used the following playbook

- Use conversations to identify a industry problem

- Look for industry partners to collaborate on solving that problem

- Cold outreach to industry partners pitching a project

It does not matter what reason enables you to launch. All that matters is that you launch because launching enables you to learn 10x faster.

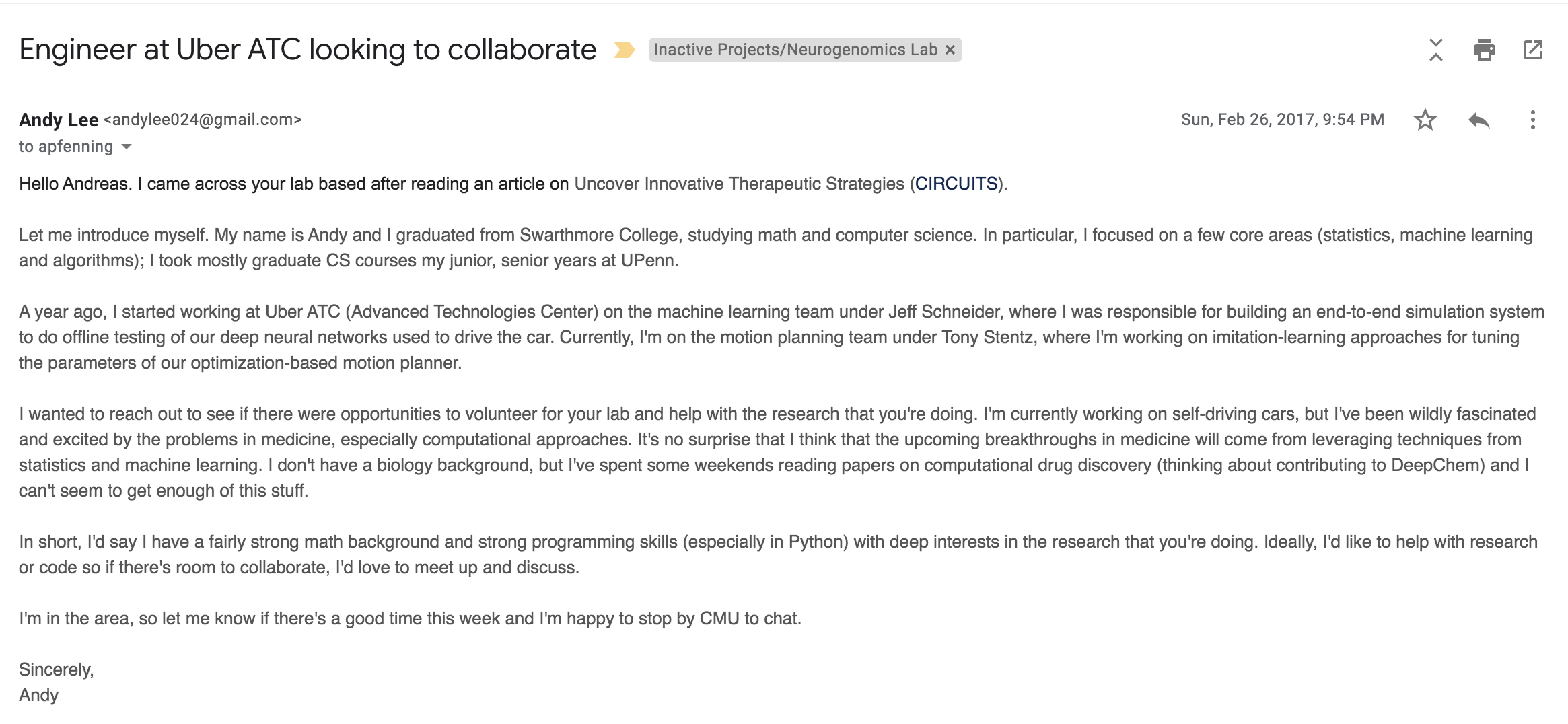

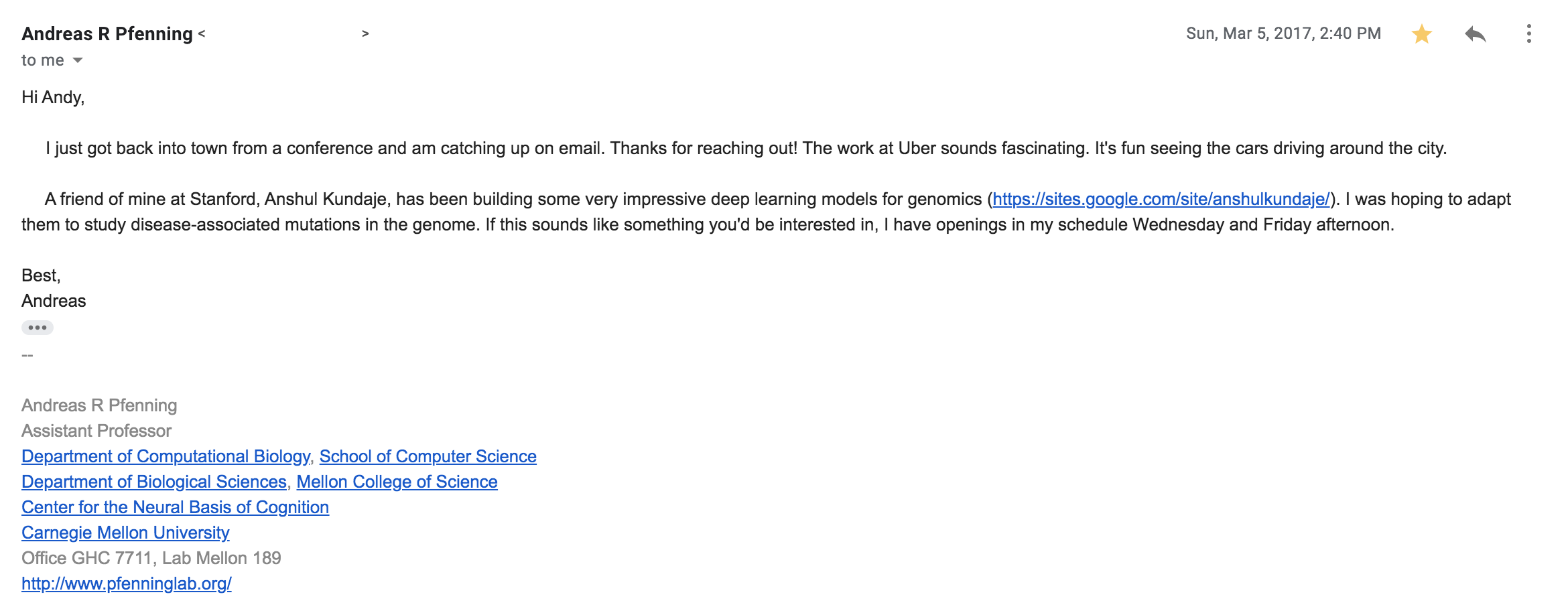

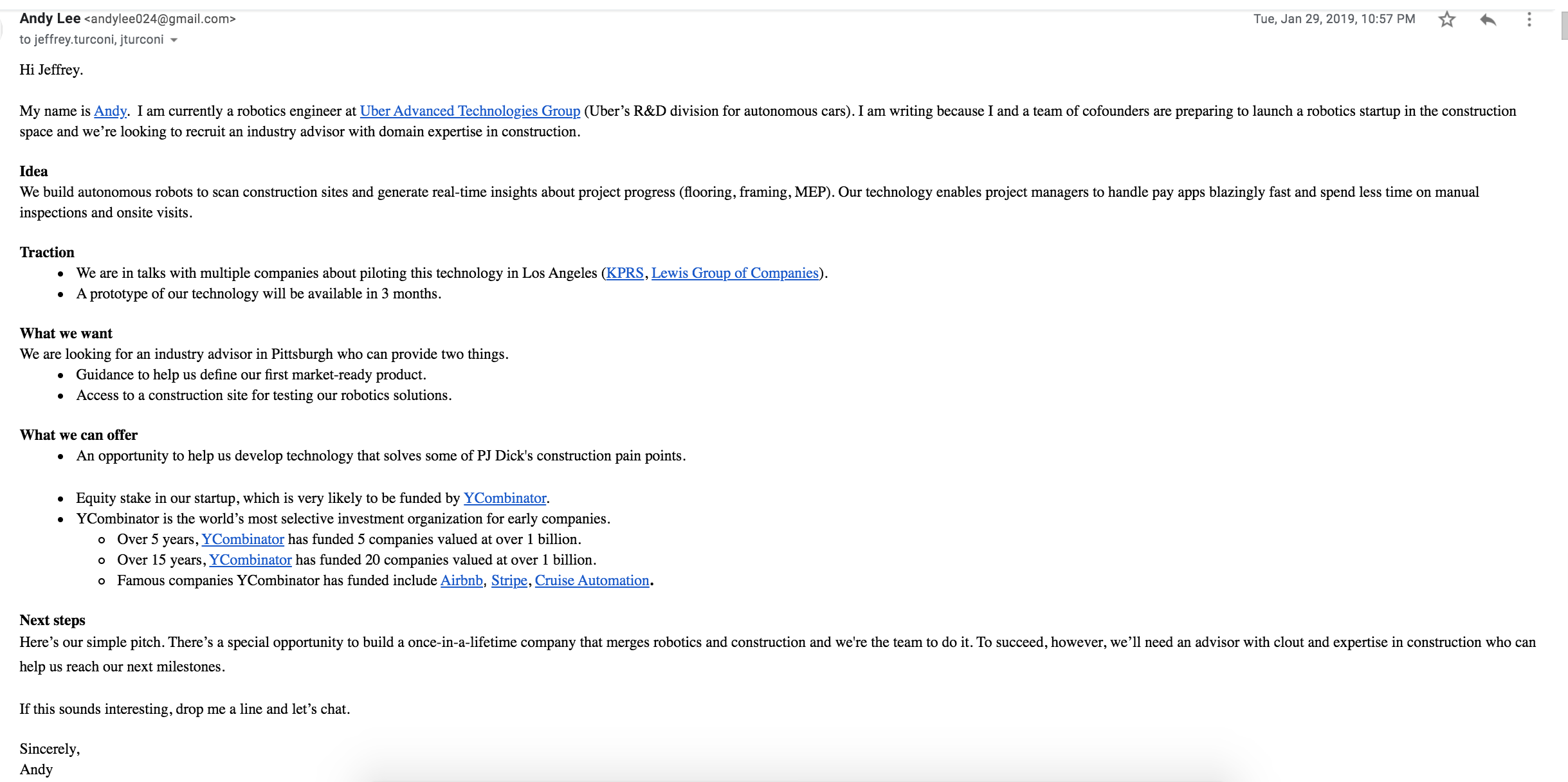

For Ikigai, I launched by volunteering to do research with a computational biology lab called the Pfenning Lab at Carnegie Mellon University. For basis, I launched by collaborating on a robotics project with with PJ Dick, the the largest construction company in Pittsburgh. Building sandboxes is an art so I copied the original emails I used to build these sandboxes.

Emails for launching Ikigai

Emails for launching basis

In my case, launching a research project the Pfenning lab unlocked rich insights about designing a drug for Alzheimer's because I was able to tour biology labs, discover how data pipelines are created in biology and hear first-hand the challenges lab members had when running Alzheimer's experiments. Collaborating with PJ Dick exposed me to real construction sites. I saw actual construction photos and witnessed the common spreadsheet templates that the construction industry used to document progress. If conversations are the ember sparks for startup ideas, then a sandbox ignites a raging inferno for startup ideas. With a sandbox in place, the process around innovation becomes straight-forward.

- Look for problems by talking to experts and observing their day to day

- Identify a problem

- Launch a product

- Gather feedback

- Move fast and repeat until you get traction (e.g. signed LOI, revenue)

What is non-obvious is how often early ideas will be wrong. Even more non-obvious is just how inconsequential being wrong really is. What matters is building a process around shipping products quickly because shipping unlocks learning and learning leads to good outcomes (e.g. discovering a product that is impactful). My cofounder Kevin and I did 3 product launches across 6 months before arriving at what basis is currently building - a CRM for trade contractors. It took us 4 months to launch our first idea (autonomous robots to scan construction sites). It took us 1 month to launch our second idea (a construction analytics platform). It took us 1 weekend to launch our third idea (a CRM for trade contractors).

We didn't necessarily get smarter each time.The key skillset we developed was shipping faster and figuring out creative ways to learn faster. Hence, the central question to ask is not

Is this a good idea?

rather,

What can I do to learn faster so that I can position myself to find a good idea?

100% Founder Conviction

The startup world points to product-market-fit as the single most important milestone for a company. I actually think the most important milestone is a concept called 100% founder conviction and it refers to the moment when the founders develop unshakable conviction that their idea will work. I didn't have 100% founder conviction for Ikigai, but I do for basis. While I cannot describe this feeling, I remember the exact moment it happened.

For months, we struggled to generate traction for our first two construction ideas. Demos were hard to come by, despite 100s of emails. I always felt like the reception to our product was lukewarm during demos. Even when we generated revenue, I felt like construction companies gave us pity deals, where the money came out of a small innovation budget used to experiment with new technologies.

Our CRM idea was different. Within a week of launching, we booked a demo through a cold call with Bent Electrical Contractors! A week later, we demo'd the product and Bent Electrical signed a contract. In the next month, In that first month, we signed 3 customers (Bent Electrical Contractors, Caldwell Electric and Wies Drywall). This was more deals than we had ever booked for all our previous ideas combined. Each sale was smooth and I felt this "aha" reaction from each of customer, where they nodded and said "this is pretty useful". Unlike our previous ideas, none of these early customers paid attention to how small we were as a company or how ugly our initial solution looked (and trust me it was ugly). All that mattered was that basis solved a painful business problem and they wanted that business problem solved immediately.

I suspect the 100% founder conviction for basis stems from my personal belief that basis is solving a real problem and that many, many people in the world have this problem. This doesn't mean that we don't face challenges.

- We might fail to sell our product fast enough before we run out of money

- We might not convince investors to give us seed capital

- We might have trouble inspiring employees to join us

The difference is that all those challenges feel tractable. Like product-market-fit, 100% founder conviction is not quantifiable, but it's this special moment when the mindset shifts from > Will this idea work? to > This idea will work. We just need to generate the proof points that will convince the world of such.

Focus on finding 100% founder conviction because the moment you find it, you'll find a way to will your company into existence regardless of obstacles.

Some advice to my younger self

For the first 7 years of my startup journey, I could never be sure if I were making progress. Lots of sleepless nights. Lots of moments where I felt like a loser, chasing impossible dreams. I'm sure a lot of founders feel this way. I'm sure a lot of successful founders once felt this way. So much of what makes startups difficult in the beginning is the psychological burden of uncertainty.

- Am I making progress on my startup?

- How should I define progress for my startup?

- When will a promising idea appear?

- How do I get initial traction?

If I could go back in time, I'd tell my younger self to just focus on 2 things.

- Rate of learning: Am I learning quickly about my space and idea?

- 100% founder conviction: Have I found 100% founder conviction?

Looking back, I wish I spent less time reading TechCrunch articles featuring big fundraises or VCs discussing post-PMF concepts (network effects, sales efficiencies, LTV/CAC) because none none of that matters in the early days. If anything, that content is detrimental for early-stage founders.

I wish more founders wrote about how they discovered ideas and how they generated early-traction. I wish more founders wrote about their origin stories. These stories move people and I sometimes think a dearth of these stories prevents a lot of talented people from building startups, people who could otherwise have outsized impacts on the world.

Notes

Note 1

Although Ikigai was accepted to YC S18, my cofounder and I split the very next day and YC rescinded our acceptance. In hindsight, this was a blessing because this was the catalyst for basis and finding the right cofounder.

Note 2

Thanks to Rohit Mulani, Sun Park, Erin Smith, Byron Wang for reading drafts.

1↩