This technical blog post covers the amyloid-beta hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Recall that Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by a number of disease phenotypes including loss of memory, loss of speech and mood swings. The amyloid-beta hypothesis provides a biological explanation for Alzheimer’s disease by positing that neurodegeneration and its resulting phenotypes is caused by an abnormal accumulation of amyloid-beta peptides. In short, the leading hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease states that too much of the amyloid-beta plaque is found in brains and this causes problems with the brain.

This is easily the most popular explanation for Alzheimer's and the amyloid-beta peptide has received perhaps the most the attention among the scientific community for AD. In this technical blog post, I'll be presenting an overview of the amyloid-beta hypothesis. My aim is to provide a thorough review of the biology behind this hypothesis to non-experts.

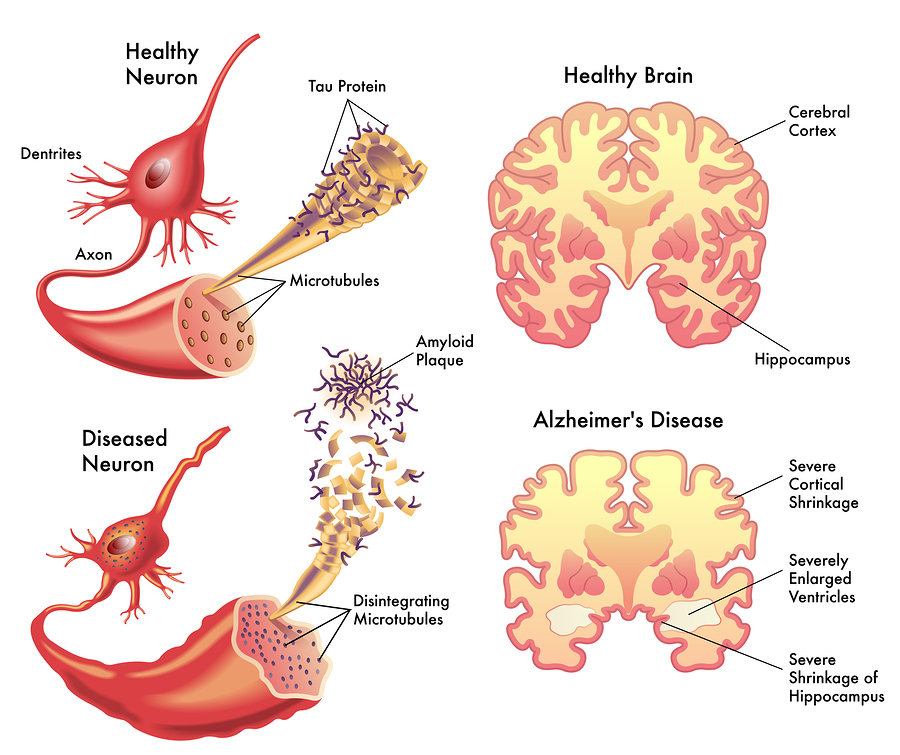

Amyloid Beta in Alzheimer's Brain. Image courtesy of 1

Amyloid Beta in Alzheimer's Brain. Image courtesy of 1

I'll be organizing my presentation as follows.

Section 1 discusses the origins of the amyloid-beta hypothesis and explain why this particular hypothesis is popular.

Section 2 discusses the biology behind the amyloid-beta peptide (how it is created and its role in mammalian bodies).

Section 3 discusses the links between the amyloid-beta peptide and Alzheimer’s Disease.

Section 4 discusses recent challenges to the amyloid-beta hypothesis and argues that the amyloid-beta hypothesis is an insufficient model for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Motivation

To begin our discussion, I would like to highlight a few trends surrounding Alzheimer’s Disease. Every single review of Alzheimer’s disease that I have come across opens by discussing the amyloid-beta hypothesis and I suspect that every credible review of Alzheimer’s disease provides some remark regarding Alzheimer’s and amyloid-beta. In addition, the only Alzheimer’s drugs that have been approved by the FDA target the amyloid-beta peptide by inhibiting the expression of amyloid-beta. 2

These two observations reflect the popularity amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease research, establishing amyloid-beta as one of the primary research directions for understanding the disease. Naturally, we want to ask the question.

What is amyloid-beta and why is it so important in Alzheimer’s Disease?The answer turns out the deceptively simple. Over the last few decades we have dissected many brains of people who exhibited Alzheimer’s disease symptoms such as the gradual loss of memory, deteriorating speech abilities, etc. Subsequently, when comparing healthy brains and disease brains, the scientific community has observed that disease brains tend to have severe neuron loss as well as an overabundance of amyloid beta peptides in contrast to their healthy counterparts.

In a previous technical blog-post, I discussed both the importance and difficulty in identifying accurate biomarkers that signal the onset of Alzheimer’s. In the context of biomarkers, amyloid-beta is perhaps the single most consistent biomarker that has been observed in post-mortem disease brains. For this reason, amyloid-beta and its overabundance provides a first clue towards understanding the biology of Alzheimer’s disease.

Amyloid Beta Biology

Before diving into the specifics of how amyloid-beta disrupts the brain and is linked to Alzheimer’s disease, I think it's important to first cover some basic biology surrounding the amyloid-beta peptide. To that end, let's try to answer the following questions. - What is the amyloid-beta peptide? - What major mechanisms are involved in the creation of the amyloid-beta peptide? - What function does the amyloid-beta peptide serve in our bodies?

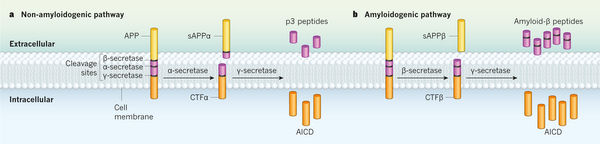

Amyloid Beta Progression. Image courtesy of 3

Amyloid Beta Progression. Image courtesy of 3

Basic building blocks: DNA, amino-acids, proteins

To begin, let’s review some basic biology. Recall that an amino-acid is defined to be sequence of nucleotide bases, specifically of length 3. Amino acids are important because there are a total of 20 amino acids that form every single protein found in complex organisms on Earth. Peptides are defined to be chains of roughly 36-43 amino-acids and proteins are defined to be sequences of peptides or amino-acids. The important thing to note is that the amino-acid, peptide and protein represent the basic building blocks or structures of complex organisms organized according to increasing complexity respectively. There is a natural composition of structure (peptides are chains of amino-acids and proteins are chains of both peptides as well as amino-acids).

Roots of Amyloid-Beta Peptide

Amyloid Beta Pathway. Image courtesy of 4

Amyloid Beta Pathway. Image courtesy of 4

We will now consider how the amyloid-beta peptide is formed and the biological mechanisms involved. It turns out the process of creating the amyloid-beta peptide is similar to a full-stick of carrot that gets sliced into 3 smaller pieces.

The amyloid-beta peptide associated with Alzheimer’s Disease originates from a larger structure called the amyloid-precursor protein (APP), expressed by the APP gene. In the context of our analogy, APP is the large carrot. The APP is then sliced by way of secretases (beta-secretase and gamma-secretase), which are biological structures designed to slice proteins into smaller pieces. One can think of these secretases as knives that slice into the larger carrot at one particular spot; the resulting carrot pieces are the amyloid-beta peptides that we have been discussing.

With this analogy in place, we can now fill in some biological details. The amyloid-precursor protein is defined to be an integral membrane protein, which refers to a protein that is attached to the membrane of a cell. While the exact function of the APP is not known, this protein is concentrated in the synapse of neurons, which suggests that it plays a role in synapse formation and neural plasticity. The secretases (beta-secretases, gamma-secretases) function to cleave integral membrane proteins (e.g. APP) into smaller pieces and they work by always acting on a specific cleavage site in the protein itself. Through this cleavage of the APP, a smaller subcomponent of the original APP is separated, which is what we refer to as amyloid-beta peptide.

Up to this point, we have discussed how amyloid-beta peptides are created. In addition, it seems plausible that amyloid-beta by its association with its parent protein APP may be linked to neural plasticity and synapse formation.

Amyloid Beta's connection to Alzheimer’s Disease

At this point, we have discussed some of the basic biology behind the amyloid-beta peptide, but we have not yet made explicit the connections between the amyloid-beta peptide and the symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The question we want to ask is

How does the over-accumulation of amyloid-beta peptides found

in AD patients contribute to memory loss and neuron death?It turns out the answer is unclear and a lot of research has been expended to try and figure this question out with only minor progress. In this section, we outline a few ways of approaching this question.

Genetic Mutations

When examining any disease, one of the first areas to look at genetic mutations. What if there was a single mutation in the genome that was present in all AD patients, but not healthy patients? This would provide an additional insight into the disease on top of the accumulation of amyloid-beta. Unfortunately, AD is a complex disease and we have not found a single genetic mutation that explains the disease.

Recall, however, that amyloid-beta peptides is created from a multi-step process (APP gene gets cleaved by secretases and then forms amyloid-beta peptides). It turns out, by virtue of GWAS (genome-wide association studies), we have discovered that certain mutations in the APP gene as well as PSEN1, PSEN2 (genes controlling the beta-secretases and gamma-secretases) significantly increase one’s risk of contracting Alzheimer’s disease. In short, a link between the genes that control the creation of the amyloid-beta peptide and Alzheimer’s disease has been established.

We refer to cases where a genetic mutation causes AD as “familial AD” because these potentially deleterious mutations are passed on from generation and generation. For familial AD cases, the link between genes and AD is promising because it means that we can now develop drugs and therapeutics to act directly one these genes to inhibit the effects of Alzheimer’s disease.

Non-genetic Mutations

Of course, there is always a caveat to complex diseases. Familial AD only represents about 5% of total AD cases, which means for the other 95% of AD patients, the cause for AD is not genetic. This makes the disease incredibly hard to treat.

For genetic diseases, the underlying cause of the disease is one or more mutations that causes some deleterious effect. The cure then becomes determining the effect of the mutation and counteracting it accordingly. When the disease is not strictly genetic (which encompasses non-familial cases of AD), there is no marker like a mutation in the gene that implies AD. Without this signaling marker, we have no idea what biological mechanism is functioning incorrectly and causing AD, which means we cannot design a drug to inhibit this mechanism. Put another way, with genetic diseases the cause is well-known (i.e. genetic mutation), but with non-genetic disease the cause is unknown. Consequently, for non-genetic disease, we have to identify the cause of the disease through other means which historically has been quite difficult given the state of our technology and understanding of biology.

In a future blog post, I will discuss current research directions for handling non-familial AD.

Challenging Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis

There are a number of challenges to the amyloid-beta hypothesis.

Over the last few years, we have developed drugs that have successfully inhibited the production of the amyloid-beta peptide. Unfortunately, even this does not slow down the onset of AD, let alone cure the disease. I think this provides perhaps the strongest evidence that AD is far too complex to be explained by amyloid-beta alone.

In fact, there are a growing number of researchers that believe AD needs to be viewed as a disease that affects numerous systems all of which have interdependent components with sophisticated interactions. These alternative hypotheses are focusing are various factors of human-biology (protein-misfolding, immune-responses) that may give additional insights into AD. For those interested, I think 5 provides a very good overview of alternative hypotheses to the amyloid-beta hypothesis.

Conclusion

To conclude, the amyloid-beta hypothesis simply states that an over-abundance of amyloid-beta peptides leads to intermediate effects like synapse loss, neuron death, ultimately leading to Alzheimer’s disease. Exactly how those amyloid-beta invite these intermediate effects is still an open research question.

Of course, this is only one explanation of Alzheimer’s disease and there is a significant amount of evidence that also suggests there are inconsistencies with this explanation. Nevertheless, the amyloid-beta hypothesis continues to be the most popular explanation of Alzheimer’s disease and the direction in which most Alzheimer’s research follows.